Author. Jasna Koteska, "The Ideology of Consumerism in Kierkegaard's Repetition"

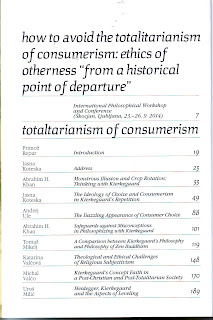

Book. Soren Kierkegaard, International Workshop and Conference: How to Avoid the Totalitarianism of Consumerism, ed. Dr. Primoz Repar, KUD Apokalipsa and Central European Institute Soren Kierkegaard (CERI-SK), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2015, 49-87.

Jasna Koteska

The Ideology of Choice and Consumerism in Kierkegaard’s Repetition

I. Introduction:

Three Impossible Choices

The following article analyzes Kierkegaard’s ideology of choice - a concept central to both the construction of subjectivity and the ideology of consumerism - as presented in Kierkegaard’s book Repetition (1843). Before delving into the analysis of choice in Repetition, we will offer the following two points about Kierkegaard’s general theory of choice.

A)

According to Kierkegaard, humans are torn between two incongruent and often contradictory paradigms: the aesthetical and the ethical one (which are more concretely visible in the two ideological commands: pleasure or duty). The ethical and the aesthetical paradigm cannot always coexist one next to another, both according to the social standards, but also because of the general incongruity of pleasure and duty, two things which contradict each other completely (“If I elect pleasure, I will immediately negate duty, and vice versa”). Not only are the contradictory commands imposed upon people by the ideological demands of the society, but people have to make their choices based on what Kierkegaard called “the leap of faith”, i.e. without a clear knowledge of the consequences of the choices made. Yet, choices are not impossible, and for Kierkegaard, most of what is out there are only some practical decisions about what kind of life one wants to commit oneself to. Although made by the “leap of faith”, people are capable of deciding, capable of making choices, depending on their subjective judgments, and on the circumstances of their lives. A perfect illustration of the problems with the choice, one finds in Kierkegaard’s most famous book Either/Or (1843), which as is well known, investigates the two paradigms from the perspective of marriage (especially in its small novelette The Seducer’s Diary). The book has two perspectives: either talks about life from an aesthetic point of view, and or talks about the life from the ethical point of view. The main argument of the second volume of Either/Or can be summed up to these few lines: A and B know each other, A is an aesthete, he is unhappy, and he is 7 years younger than B. B is married and at first he writes to A to tell him that he considers that marriage possesses an aesthetic value (and pleasure). A is not convinced. B then writes again and this time he includes the ethical dimension (and duty), too. A does not respond again. B finally sends his third letter, in which he retells a narrative told by a priest that humans are always wrong in relation to God, which basically means that the project is finalized with the short religious tractate. A continues to be silent.

B)

Either/Or introduced the third, religious paradigm. Both choices, the aesthetical (“the life of a poet”) and the ethical (“the life of a judge”), according to Kierkegaard are incomplete, the only resolution of human’s destiny must come about in the form of a religious choice. But, due to the radical antagonism of human situation, the third choice (“the life of a priest”, or broadly: “the life of a believer”), also possesses an imbedded paradox within itself. The paradox consists of the fact that humans are incapable of bypassing the abyss between the finite and the infinite, and modern life in the mid-19 century only fosters this impossibility. Kierkegaard left a testimony regarding a strange shift in the concept of a belief. A human is already someone who can no longer simply and directly “believe”. If he/she believes it is only with the help of rituals, always with a pinch of doubt, and most important – no longer a belief in God, but only a belief in believing. Therefore, the real problem for Kierkegaard no longer was to prioritize between the ethical and the aesthetical paradigm, between pleasure and duty, but the more urgent question of how and if a person can still make a genuine religious choice? Is the religious choice still possible for humans? Can a person choose to fundamentally believe without cynicism, as, for example, without having the dilemma: “But, what if Abraham’s choice to kill Issac was not a religious call, but just his own private madness”?[1]

The analysis which follows offers the reading of these dilemmas in Kierkegaard’s book Repetition (1843). Although a small fraction in the big body of his thought, Repetition is a magnificent door into Kierkegaard’s theory of choice, as in its core, it is essentially a book about the problem of choice. The book was published in 1843, Kierkegaard’s most prolific year, when he also published Either/Or and Philosophical Crumbs. In his journals, Kierkegaard didn’t have a high opinion of Repetition, as he considered it: “Insignificant, without any philosophical pretension, a droll little book, dashed off as an oddity”.[2] Our analysis will try to offer that the book, in fact, is a kind of Kierkegaardian “manifesto of choice”; a complicated inquiry into three concepts which gravitate around the problem of choice: movement, repetition, and farce.

As is the case with most of Kierkegaard’s books, Repetition is a highly heterogeneous book: it opens as a philosophical tractate about the differences between repetition and recollection, it continues as a theatrical review of a farce, and it ends as an epistolary exchange of letters between the narrator and the young unnamed man. The unnamed man is unhappily in love; the narrator decides to mentor his love affair, although not in the most empathic way. The narrator offers to help his epistolary friend, but more as a psychological experiment, therefore the subtitle of the book: An Essay in Experimental Psychology. The advice the narrator gives, can be summed up as follows: 1) love is an impossible goal, 3) the young man needs to destroy his connections to the loved girl, 3) he needs to search for a new love and 4) only by means of repetition he can regain his happiness again.

The book was published by pseudonym Constantine Constantius. Kierkegaard’s use of pseudonyms was less intended to provide anonymity for the author (most of the people in Copenhagen knew who wrote them),[3] but to serve his main thesis: Constantine Constantius translates as Constant Constant, a name which suggests both the affirmation of repetition, but at the same time the affirmation of the constancy of repetition. The central questions for Kierkegaard in Repetition are: Does movement exist at all? If it does exist, is it possible to achieve constancy by stand stilling the motion? Is it possible to freeze the world flux? Can the change (and by extend, the choice) be understood as a movement of constancy? Can life be seen as a movement around one constant center, around which, every new circulates, only in so far as to affirm the impossibility of the new arriving? Can the repetition be seen as a “the kind of change” in the direction of the constancy?[4] Or, vice versa, is constancy impossible? Is repetition impossible? Are humans doomed to seek the new, always the new? And if later is the case, is the ideological landscape constructed in such a way that the tyranny of choice, the tyranny of consumerism, and the circulation of goods, are deeply imbedded in the tissue of the external reality? In the following pages we will seek answers to these questions through several notions which Kierkegaard developed on the pages of Repetition, regarding the choice and consumerism: movement, repetition and farce.

...

The rest of the text is unavailable due to copyrights of the book:

Koteska, Jasna, Kierkegaard On

Consumerism (The Aesthetic, The Ethical, and the Religious Reading),

Publisher: Kierkegaard Circle, Trinity College, University of Toronto and the CERI-SK, Ljubljana, September, 2016.

References

DI PERNA, A. (1996): “Ozzy Osbourne meets Marilyn Manson and All Hell Breaks Loose”. Guitar World, June 1996.

www.mansonwiki.com/wiki/Interview:1997/06_Guitar_World. Accessed: September 5, 2014.

EAGLETON, T. (2008): Literary Theory: An Introduction. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

FREUD, S. (2008): Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

FREUD, S. (2001): SE Pre-Psycho-Analytical Publications and Unpublished Drafts, I (1886-1899). Ed. James Strachey. London: Vintage.

HARTSHORNE, S. (2014): “I Was a Woman Laughing Alone with Salad, it’s Really Not that Funny”. The Guardian, March 5, 2014.

www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2014/mar/05/woman-laughing-alone-with-salad. Accessed: September 5, 2014.

HONG, V. H. in HONG, H. E. (Ur.) (2000): The Essential Kierkegaard. New Jersey: Princeton University.

http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html. Accessed: SSeptember 5, 2014.

JANOUCH, G. (2012): Conversations with Kafka. Introduction of Francine Prose. New York: New Directions.

KIERKEGAARD, S. (2009): Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MARX, K. (1975): Kapital. Zagreb: Školska knjiga. (Slov. prev.: Kapital: kritika politične ekonomije, Sophia, Ljubljana 2012, prev. Mojca Dobnikar.)

MARX, K. in ENGELS, F. (2004): Communist Manifesto. V: Communist Manifesto/ Wages, Price and Profit/Capital (selections)/Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. London: CRW Publishing Limited.

MOONEY, F. E. (2009): “Introduction”. In: Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press.

SEDLER, M. (1983): „Freud’s Concept of Working Through“. In: Psychoanalytic Quaterly, No. 52.

WHEEN, F. (2006): Marx’s Das Kapital. A Biography. London: Atlantic Books.

WILSON, S. W. (1968): “Prince of Boredom: The Repetitions and Passivities of Andy Warhol”. Art and Artists, No. 13-15, March. Pittsburgh: Archives of museum of Andy Warhol.

The Business Artist: How Andy Warhol Turned a Love of Money into a 228 Million Dollar Art Career. Hufftington Post, 12/16/2010 Accessed: September 5, 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/artinfo/the-business-artist-how-a_b_797728.html

WEBER, S., SMITH, T. (1996): “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image” (A Discussion, Power Institute of Fine Arts, University of Sydney), 16. september).

ŽIŽEK, S. (2007): Only a Suffering God Can Save Us. Lacanian Ink, No. 26. lacan.com/zizmarqueemoon.html, 6th of September, 2014.

ŽIŽEK, S. (2009): First as Tragedy, Than as Farce. London – New York: Verso.

[1] Žižek, Slavoj. “Only a Suffering God Can Save Us”, (Lacanian Ink, No. 26, 2007), lacan.com/zizmarqueemoon.html, Accessed September 6, 2014.

[2] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, a new translation by M.G. Piety (Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 2009), x.

[3] Mooney, F. Edward, “Introduction” in Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, a new translation by M.G. Piety (Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 2009), xi.

[4] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 177.

[6] Freud, Sigmund, Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008), 21.

[7] Freud, Sigmund, SE Pre-Psycho-Analytical Publications and Unpublished Drafts, Volume I (1886-1899), ed. James Strachey, (London: Vintage, 2001), 367.

[8] Marx, Karl (with Friedrich Engels). Communist Manifesto in: Communist Manifesto/ Wages, Price and Profit/Capital (selections)/Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (London: CRW Publishing Limited, 2004), 19.

[9] Marx, Karl. Kapital (Zagreb: Školska knjga, 1975), 11.

[10] Wheen, Francis. Marx’s Das Kapital. A Biography, (London: Atlantic Books, 2006), 39.

[12] Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Than as Farce, (London, New York: Verso, 2009), 139.

[14] Marx Karl, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, as cited in: Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Than as Farce, 1.

[15] Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Than as Farce, 52-54.

[16] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 22-23.

[18] DiPerna, Alan. “Ozzy Osbourne meets Marilyn Manson and All Hell Breaks Loose”, Guitar World, June 1996.

Accessed: 5 September 2014: www.mansonwiki.com/wiki/Interview:1997/06_Guitar_World

[19] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 20.

[20] The Essential Kierkegaard, edited by Howard V. Hong and Edna. H. Hong, New Jersey: Princeton University, 2000, 252.

[21] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 26-28.

[22] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image” (A Discussion, Power Institute of Fine Arts, University of Sydney), September 16, 1996), Accessed September 5, 2014:

http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[23] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 32.

[24] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image”, http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[25] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 29.

[26] Janouch, Gustav. Conversations with Kafka. Introduction by Francine Prose, (New York: New Directions, 2012), 159.

[27] Hartshorne, Sarah. “I Was a Woman Laughing Alone with Salad, it’s Really Not that Funny”, The Guardian, 5 March, 2014. Accessed 5 September 2014:

www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2014/mar/05/woman-laughing-alone-with-salad

[28] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image”, http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[29] William S. Wilson. “Prince of Boredom: The Repetitions and Passivities of Andy Warhol”, (Art and Artists, No. 13-15, March 1968), Archives of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

[30] The Business Artist: How Andy Warhol Turned a Love of Money into a 228 Million Dollar Art Career. Hufftington Post, 12/16/2010 (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/artinfo/the-business-artist-how-a_b_797728.html)

[31] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 18.

[32] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image”, http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[33] Sedler, Mark. „Freud’s Concept of Working Through“, (in: Psychoanalytic Quaterly, No. 52, 1983), 90.

[34] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 39.

[35] Eagleton, Terry, Literary Theory: An Introduction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 160.

[36] Lacan, Jacques. Četiri temeljna poima psihoanalize (Zagreb: Naprijed, 1986), 255.

[39] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 33.

[40] Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny (Introduction by Hugh Haughton, Penguin Classics, 2003), xivi.

[41] Mooney, F. Edward, “Introduction” in: Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, xiv.

[42] Moony says: “His ‘despair’ can seem like a hysterical affectation, just ‘too much drama’ to be credible”. But the young man’s despair is in fact – credible, at least in the sense discussed previously as the question of choice in Freud. Just as in Kierkegaard the anxiety of humans steams from the impossibility to choose, in Freud too, the impossibility to choose is the origin of hysteria (see the chapter: Freud: Psychology of Movement from the first part of this article).

[43] Marx: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great events and characters of world history occur, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”.

[i] Žižek, Slavoj. “Only a Suffering God Can Save Us”, (Lacanian Ink, No. 26, 2007), lacan.com/zizmarqueemoon.html, Accessed September 6, 2014.

[ii] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, a new translation by M.G. Piety (Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 2009), x.

[iii] Mooney, F. Edward, “Introduction” in Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, a new translation by M.G. Piety (Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press, 2009), xi.

[iv] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 177.

[vi] Freud, Sigmund, Five Lectures on Psychoanalysis, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008), 21.

[vii] Freud, Sigmund, SE Pre-Psycho-Analytical Publications and Unpublished Drafts, Volume I (1886-1899), ed. James Strachey, (London: Vintage, 2001), 367.

[viii] Marx, Karl (with Friedrich Engels). Communist Manifesto in: Communist Manifesto/ Wages, Price and Profit/Capital (selections)/Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (London: CRW Publishing Limited, 2004), 19.

[ix] Marx, Karl. Kapital (Zagreb: Školska knjga, 1975), 11.

[x] Wheen, Francis. Marx’s Das Kapital. A Biography, (London: Atlantic Books, 2006), 39.

[xii] Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Than as Farce, (London, New York: Verso, 2009), 139.

[xiv] Marx Karl, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, as cited in: Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Than as Farce, 1.

[xv] Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Than as Farce, 52-54.

[xvi] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 22-23.

[xviii] DiPerna, Alan. “Ozzy Osbourne meets Marilyn Manson and All Hell Breaks Loose”, Guitar World, June 1996.

Accessed: 5 September 2014: www.mansonwiki.com/wiki/Interview:1997/06_Guitar_World

[xix] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 20.

[xx] The Essential Kierkegaard, edited by Howard V. Hong and Edna. H. Hong, New Jersey: Princeton University, 2000, 252.

[xxi] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 26-28.

[xxii] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image” (A Discussion, Power Institute of Fine Arts, University of Sydney), September 16, 1996), Accessed September 5, 2014:

http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[xxiii] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 32.

[xxiv] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image”, http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[xxv] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 29.

[xxvi] Janouch, Gustav. Conversations with Kafka. Introduction by Francine Prose, (New York: New Directions, 2012), 159.

[xxvii] Hartshorne, Sarah. “I Was a Woman Laughing Alone with Salad, it’s Really Not that Funny”, The Guardian, 5 March, 2014. Accessed 5 September 2014:

www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2014/mar/05/woman-laughing-alone-with-salad

[xxviii] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image”, http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[xxix] William S. Wilson. “Prince of Boredom: The Repetitions and Passivities of Andy Warhol”, (Art and Artists, No. 13-15, March 1968), Archives of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh.

[xxx] The Business Artist: How Andy Warhol Turned a Love of Money into a 228 Million Dollar Art Career. Hufftington Post, 12/16/2010 (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/artinfo/the-business-artist-how-a_b_797728.html)

[xxxi] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 18.

[xxxii] Weber, Samuel with Smith, Terry. “Repetition: Kierkegaard, Artaud, Pollock and the Theatre of the Image”, http://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/WritingScience/etexts/Weber/Repetition.html

[xxxiii] Sedler, Mark. „Freud’s Concept of Working Through“, (in: Psychoanalytic Quaterly, No. 52, 1983), 90.

[xxxiv] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 39.

[xxxv] Eagleton, Terry, Literary Theory: An Introduction (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 160.

[xxxvi] Lacan, Jacques. Četiri temeljna poima psihoanalize (Zagreb: Naprijed, 1986), 255.

[xxxix] Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, 33.

[xl] Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny (Introduction by Hugh Haughton, Penguin Classics, 2003), xivi.

[xli] Mooney, F. Edward, “Introduction” in: Kierkegaard, Søren: Repetition and Philosophical Crumbs, xiv.

[xlii] Mooney says: “His ‘despair’ can seem like a hysterical affectation, just ‘too much drama’ to be credible”. But the young man’s despair is in fact – credible, at least in the sense discussed previously as the question of choice in Freud. Just as in Kierkegaard the anxiety of humans steams from the impossibility to choose, in Freud too, the impossibility to choose is the origin of hysteria (see the chapter: Freud: Psychology of Movement from the first part of this article).

[xliii] Marx: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great events and characters of world history occur, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”.

Post a Comment